In light of recent events – in particular the statue of Edward Colston here in Bristol being pulled down and plunged into the harbour last weekend – I thought it might be worth taking a look at something not entirely unrelated: The grave of Scipio Africanus, situated in the churchyard of St Mary’s Church, Henbury, Bristol.

The grave itself is something I’ve been aware of since school; I went to Henbury School (now called Blaise High School), which has changed so much it really isn’t the same school it was when I was there; the old school was demolished and rebuilt in the mid-2000s!

While my later exam subjects included history, which I took at CSE level (and achieved a lamentable result), the syllabus for those couple of years – taught by one Mr Douglas – was modern world history, largely covering the first half of the twentieth century. The main areas I recall studying were Ireland, the period leading up to and following the Easter Rebellion, and the first world war, though we probably covered a little more than just those two specific topics. Before we reached the point where we had to choose subjects for exam studies, though, a much wider spectrum of history was taught (but as part of a broader subject, called humanities).

As well as school trips to places like Avebury to see the stone circle and the nearby West Kennet Long Barrow and Silbury Hill, or to Chepstow Castle and Tintern Abbey, we also occasionally had simpler, cheaper trips – within walking distance of the school – where we learned a little about more local history, and other matters relating to the area. One of those walking trips took us to St Mary’s Church, where we were shown the grave, and told a little about Scipio Africanus. I don’t remember much about the more general topic(s) we were covering at the time, but I think we may have been learning something about the slave trade as well; it seems logical that we would have been shown the grave within a wider context. This may very well have included Edward Colston, given that he was a slave trader whose name is reflected in various places in Bristol – but four decades or so later, I can’t be sure.

So that gives a little context about how I first came to learn about the grave’s existence – though I have to admit that I don’t remember a great deal about what we were taught at the time. Before setting out to write this, all I could have said was that he was a former slave who had been granted his freedom and worked as a servant, that his employers thought highly of him, and that he had died young, in Henbury, and was buried in that churchyard. Anything I’ve written below that goes into any more detail than that comes from the tiniest amount of information I have in one book that happens to be sitting on my shelves, and beyond that a recent walk that took me through the churchyard, and – for the main part – some subsequent use of a search engine.

The book is called The Bristol Story. Published in 2008 in graphic novel style, it provides an account of Bristol’s history from its origins up to its more recent past. At the time I found it a fascinating read, even though it’s clearly aimed at the younger reader. I still have my copy but, unfortunately, when I pulled it off the shelf this week I noticed that the spine is broken and a couple of pages in the middle have worked loose, with a split in the main binding holding the two halves either side of them together.

Since it was given away free of charge, it would be nice to find it available to download as a PDF file, but looking at the Bristol Reads website (the home page for the book) I can’t see such an obvious thing. Which is a shame, because I feel that it’s a good educational resource, even if it only lightly glosses over many topics – necessarily, because Bristol has a lot of history. It’s certainly a good starting point that could pique the interests of different students, leading them to focus on different aspects and periods of that rich history. Not having a PDF version available is a bit of a missed opportunity.

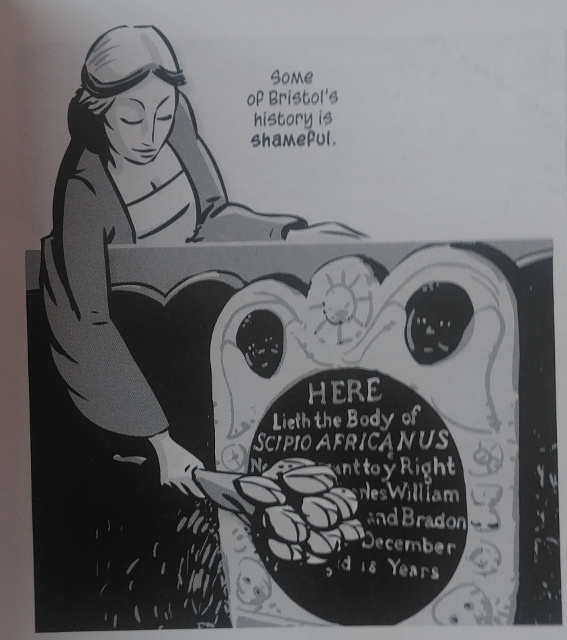

The grave of Scipio Africanus is depicted in the book very early on, with the statement that “Some of Bristol’s history is shameful” and nothing more at this point.

The woman placing flowers on the grave in that picture, incidentally, is Avona – not someone contemporary with Scipio, and not even a real person. Although you wouldn’t guess it from the image, Avona was supposed to be a giant, and was the love-interest of two other giants, Goram and Vincent. All three are part of the area’s mythology – and none are relevant to this!

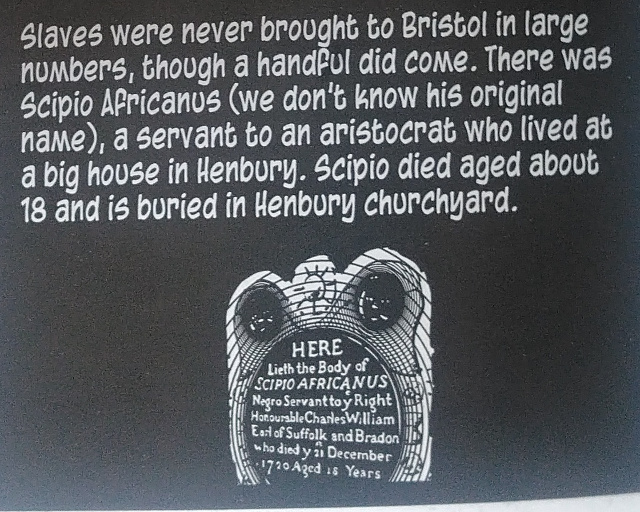

Later in the book there is a section covering slavery. This is, obviously, a part of the shameful aspect of Bristol’s history the book mentions, and the reason Colston’s statue is so controversial. It’s in this section that the grave crops up again, although its own specific mention is very small:

“Slaves were never brought to Bristol in large numbers, though a handful did come. There was Scipio Africanus (we don’t know his original name) a servant to an aristocrat who lived at a big house in Henbury. Scipio died aged about 18 and is buried in Henbury churchyard.”

That corresponds with some of what I remembered from school, which (to repeat myself) was “that he was a former slave who had been granted his freedom and worked as a servant, that his employers thought highly of him, and that he had died young, in Henbury, and was buried in that churchyard.”

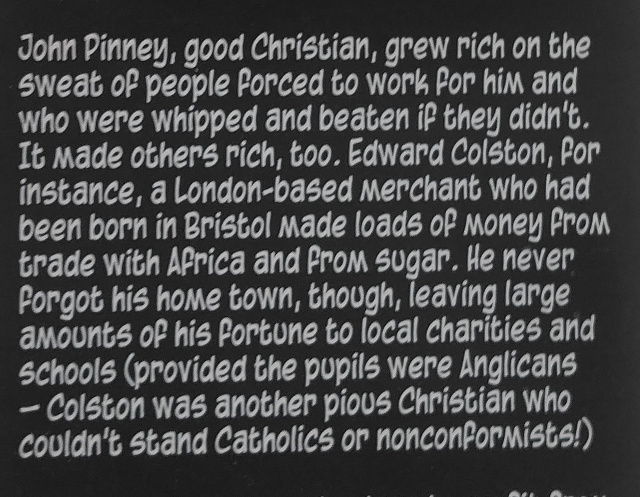

Edward Colston is also mentioned in this section, on the next page, forming the larger part of a single paragraph, itself ending a couple of paragraphs about another (later) slaver, John Pinney:

“It (slavery) made others rich, too. Edward Colston, for instance, a London-based merchant who had been born in Bristol made loads of money from trade with Africa and from sugar. He never forgot his home town, though, leaving large amounts of his fortune to local charities and schools (provided the pupils were Anglicans – Colston was another pious Christian who couldn’t stand Catholics or noncomformists!)”

Note: Although I don’t think there are, it’s possible the book contains other references to either (or both), but because of the condition of the spine and to avoid further damage, reading through it properly would be difficult. Taking photographs of the relevant parts above was hard enough!

Walking through the churchyard earlier this week gave me an opportunity to take a photograph of the grave.

It’s quite elaborate compared to most graves in the churchyard (although some of the colour may be a more recent addition – it was ‘restored’ in 2007) and features both a headstone and a footstone, with inscriptions on each. The one on the headstone reads:

“HERE Lieth the Body of SCIPIO AFRICANUS Negro Servant to y Right Honourable Charles William Earl of Suffolk and Bradon who died y 21st December 1720 Aged 18 Years”

‘Bradon’ should actually read ‘Bindon’ but, apparently, a mistake was made when the grave was restored.

And the footstone reads:

“I who was Born a PAGAN and a SLAVE

Now Sweetly Sleep a CHRISTIAN in my Grave

What tho’ my hue was dark my SAVIOURS sight

Shall Change this darkness into radiant light

Such grace to me my Lord on earth has given

To recommend me to my Lord in heaven

Whose glorious second coming here I wait

With saints and Angels Him to celebrate”

There is a brief history of St Mary’s Church on its website which highlights the grave, and gives more detail than I remembered from school (though it seems likely that this is the level of information we were actually given at the time). Summarised into bullet points:

- Very little is actually known about him.

- He was servant to Charles William Howard, 7th Earl of Suffolk.

- Howard and his wife (Arabella Astry) are believed to have lived in ‘the Great House’ in Henbury.

- How they came by Scipio is not known.

- Howard and his wife died two years later.

- There is no record of Scipio in the church registers.

- The grave is a grade II* listed building.

I’m not familiar with the Great House, so I did a quick search for that, and found a blog by archivist and architectural historian Nicholas Kingsley, called Landed Families of Britain and Ireland that mentions it in a post titled (224) Astrey of Harlington Woodend and Henbury Great House.

As an aside, the first thing I noticed on that page, before I began reading, was the coat of arms/shield, pictured at the top left of the main body of text. I may be wrong, but I think that bears more than a passing resemblance to the Henbury School badge at the time I was there. A (very quick) search online didn’t throw up any examples, and nor did a Google reverse image search based on that shield – and the current school badge is completely different, reflecting its new name. I did, however, spot a group on Facebook for the school, so I’ve now joined it – perhaps I’ll find an image of the old badge there; I’ll look further in due course.

There is a lot of detail about the house on that page, which amongst other things reveals that it was demolished early in the 19th century – but I think I now know where it was, more or less. The page also provides more information about Arabella Astry and her family – and suggests that she, too, was buried in Henbury:

“Arabella Astry (1684-1722), baptised at Henbury, 6 September 1684; occupied the Great House after the death of her mother in 1708; married, 1715 (settlement 10 June and licence 9 July), Charles William Howard (1693-1722), 7th Earl of Suffolk & 2nd Earl of Bindon, but had no issue; died 23 June 1722 and was buried at Henbury.”

That got me curious: where, exactly, is her grave? Searching further, I found that some of the information above conflicts with other sources. According to Find A Grave, for example, her date of birth is unknown, and she was buried at Waldon Abbey, while Geni claims she was born around 1693 – which Kingsley gives as her husband’s year of birth, with hers as 1684 – but agrees that she was buried in Henbury. Meanwhile, Wikipedia’s entry for Waldon Abbey mentions that the final resting place of both Charles Howard and his wife Arabella is the Howard Vault at the abbey.

All of which, while interesting, is straying off topic – so returning to Scipio Africanus…

Noting that the grave is grade II* listed, a good source of information about listed buildings is Historic England, and a quick visit and search of their website didn’t disappoint. There is an entry for the grave, which was listed on 4th March, 1977 – only a few years before the school visit (which I think would have been somewhere around 1979 to 1981). This expands even more on the detail mentioned above – but interestingly, it makes clear that most of what is known about Scipio Africanus comes from the inscriptions on the stones.

What is perfectly clear from that page is that Scipio’s origins, and how he came to be with the Howards, is unknown; neither’s families had any involvement in the West Indies or America – and therefore with the triangular trade that saw slaves transported there from Africa – so it’s likely that he found himself in the area, and therefore with them, through someone else who did have some involvement or connection.

An obvious guess at this point is that the ‘someone else’ may have been Colston, but that’s unlikely. Although he was Bristol-born, Colston’s family moved to London around the time of the English Civil War (1642-1651), when he himself was still just a child. It was in London that he eventually became involved with the slave trade, and although he did return to Bristol for a while, that was in 1684, and he left again in 1689 – before Scipio was even born. It’s more likely Scipio came to the Howards through another Bristol-based slave trader or from a previous ‘owner’.

We were told on the school trip that he was free, and this seems to have come from the first two lines of the verse on his footstone (“I who was Born a PAGAN and a SLAVE, Now Sweetly Sleep a CHRISTIAN in my Grave”). The second line seems to counter the first, suggesting that while he was born a pagan and a slave, he died a Christian – but the question is does it just mean he was no longer a pagan, or does it also mean he was no longer a slave?

Clearly some people seem to believe so, such as whichever teacher it was that took us on that walk to the church! I’m fairly sure I remember being taught at school that while Britain was involved in the slave trade, we didn’t have slaves in this country, but I’m not sure how true that was.

The headstone describes Scipio as a servant, and I began wondering what life was like for a servant at that sort of time. I soon found myself looking at the website of ‘multi-award-winning author of carefully researched novels’ (my emphasis) Charlotte Betts, who explains of domestic servants in the seventeenth century that as well as receiving low pay (not a surprise) “it was usual in those times to physically discipline the servants” – citing Samuel Pepys as an example. Pepys diary can be found online, so it’s easy to verify this. His 24th April, 1663 entry mentions beating his ‘boy’ with a salt eel (a piece of rope), for instance, while he talks of whipping him in his 21st June, 1662 entry.

To me, that doesn’t sound much better than slavery.

Of course, these diary entries are from the 1660s, the middle of the seventeenth century (as per the title of Charlotte Betts’ page) – whereas Scipio was born in or around 1702; the beginning of the eighteenth century. It’s possible things could have changed for the better by then.

Returning to the Historic England page, and the speculation about whether Scipio had been granted his freedom, it notes that there is no evidence of this, other than the second line of the verse suggesting he may have been baptised, and that there was a common belief that with baptism came freedom. According to a University of York Borthwick Institute for Archives page entitled Baptism of black servants & slaves, however, it seems that was a belief held amongst slaves themselves. The final paragraph on the page states:

“It is important to remember that in the eighteenth century there was some confusion about the status of a person brought to England as a slave: in 1762 Lord Chancellor Henley had declared that ‘as soon as a man sets foot on English ground he is free’ and although this was later successfully challenged in the courts it was widely (and erroneously) believed amongst slaves themselves that baptism set them free and thus a baptism was often a cause for great celebrations.”

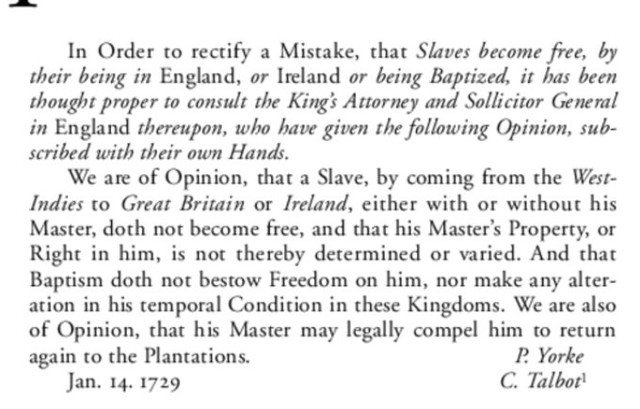

Note also what it says about the declaration, by Lord Chancellor Henley, that “as soon as a man sets foot on English ground he is free” – which was successfully challenged in the courts. And that was 1762, four decades after Scipio and the Howards had died. Coincidentally, I also happened upon something on this topic on Twitter only this morning – a thread by David Allen Green, a columnist for the Financial Times and blogger and commentator on law and policy. In that thread, he made reference to the ‘Yorke-Talbot opinion of 1729’ and included this image:

“In Order to rectify a Mistake, that Slaves become free, by their being in England, or Ireland or being Baptized, it has been thought proper to consult the King’s Attorney and Sollicitor General in England thereupon, who have given the following Opinion, subscribed with their own Hands.

We are of the Opinion, that a Slave, by coming from the West Indies to Great Britain or Ireland, either with or without his Master, doth not become free, and that his Master’s Property, or right in him, is not thereby determined or varied. And that Baptism doth not bestow Freedom on him, nor make any alteration in his temporal Condition in these Kingdoms. We are also of Opinion, that he Master may legally compel him to return again to the Plantations.”

That opinion could be be read as meaning slaves visiting the country either with their master on business, or on behalf of them (“with or without his Master”) – but the final sentence suggests to me that if a slave’s master may compel his return, that also means they could remain here, and remain a slave.

So, on the face of it, there were indeed slaves in this country – possibly temporarily, visiting on behalf of their owners, and possibly settled with them.

The thread explains that while this was delivered as an opinion, it had weight because of who Yorke and Talbot were – the Attorney General and Solicitor General, the government’s two chief law officers – and that was thirty three years before Henley made his declaration, and nine years after Scipio Africanus died. This shows that his apparent baptism shouldn’t be taken as evidence that he was free.

A Flickr post by Paul Townsend, entitled The Henbury Slave Grave says he “became much loved by the young Earl and his wife who treated him almost like a son.” That’s the only reference I’ve found to make such a bold claim – there is a difference between highly regarded (which is what I remember from school) and being treated “almost like a son” – and I found it slightly odd considering their ages. Scipio was born in 1702, and ‘the young Earl’ – Charles William Howard – in 1693; a mere nine years earlier. His wife, Arabella Astry, was born in 1684, though, so perhaps that claim refers to her rather than the both of them, given that the age difference there was eighteen years.

It becomes less odd when the grave is considered, though, due to its ornate nature. To have put so much into marking Scipio’s grave does lend weight to just how highly regarded he may have been by the Howards – perhaps they (having had no children of their own) did treat him as though he were a son. If so, it does seem plausible that while he worked as a servant for them, he did so free of the bonds of slavery.

We’ll never know, but I strongly suspect there has been some romanticising of what little we know of Scipio Africanus, and therefore what we were told at school – perhaps out of a sense of shame about Bristol’s participation in the slave trade.